The Evolution of the Concept of Hell and Satan in Jewish and Christian Thought

The Evolution of the Concept of Hell and Satan in Jewish and Christian Thought

Introduction

The transition from the Old Testament (OT) concept of Sheol to the New Testament (NT) understanding of Hell, alongside the development of Satan as a distinct and powerful entity, represents significant theological developments in Jewish and Christian thought. These changes are deeply rooted in the religious and cultural shifts that occurred during the intertestamental period, where Jewish apocalyptic literature played a crucial role in shaping the doctrines that would later be foundational to Christian theology.

Sheol in the Old Testament

In the OT, the concept of the afterlife is largely centered around Sheol, a term used to describe the abode of the dead. Sheol is depicted as a shadowy, indistinct underworld where all souls, regardless of their moral conduct in life, reside after death. It is a place of silence, darkness, and separation from the living and from God, rather than a place of torment or reward. There is no clear distinction between the righteous and the wicked in Sheol; both are thought to go there after death. References to Sheol in the OT, such as in the Psalms and Job, do not convey a detailed or systematic eschatology but rather reflect an early and somewhat vague understanding of the afterlife.

The Development of Hell in the Intertestamental Period

Between the OT and NT, significant theological developments took place, particularly during the intertestamental period, which spans from the 3rd century BCE to the 1st century CE. During this time, Jewish thought evolved under the influence of Persian, Hellenistic, and emerging Jewish apocalyptic literature. These influences contributed to a more nuanced understanding of the afterlife, where moral conduct in life was believed to have consequences in the afterlife.

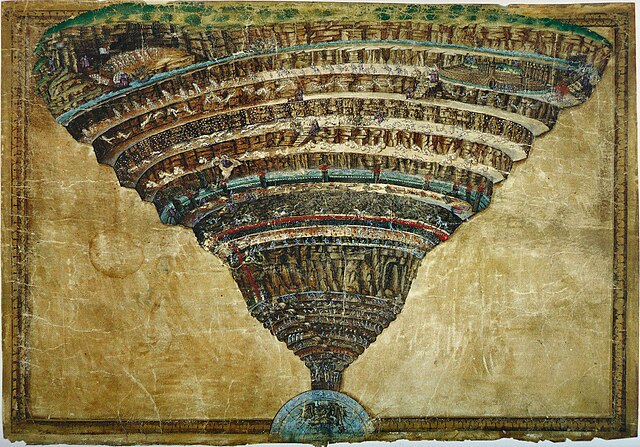

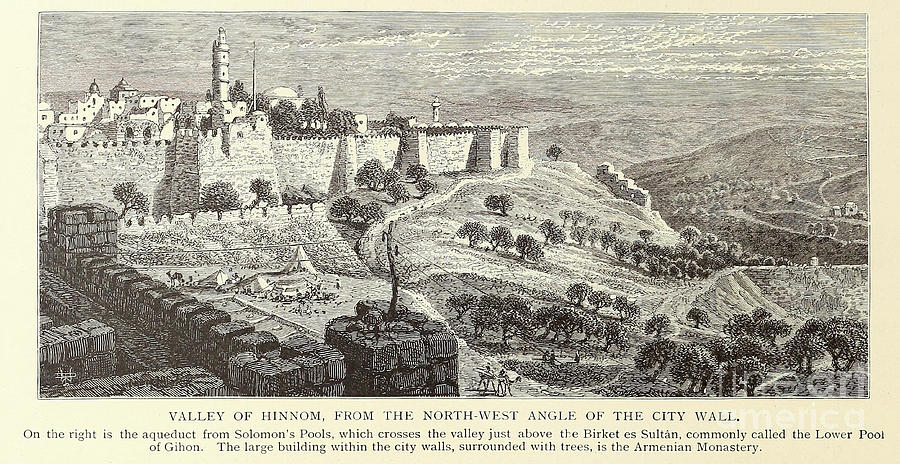

One of the most significant developments during this period was the concept of Gehenna, which in the NT is often translated as “Hell.” Gehenna originally referred to the Valley of Hinnom, a place outside Jerusalem associated with idolatry and child sacrifices (as mentioned in Jeremiah 7:31). By the time of the NT, Gehenna had become a symbol for a place of final judgment and eternal punishment for the wicked, distinct from the neutral and shadowy Sheol of the OT.

The Evolution of the Concept of Satan

Parallel to the development of Hell, the figure of Satan underwent significant transformation from the OT to the NT. In the OT, the term “Satan” (from the Hebrew satan, meaning “adversary” or “accuser”) is used more as a title than as a proper name. For example, in the Book of Job (Job 1-2), Satan appears as a member of the divine council, acting as an accuser or tester of human beings with God’s permission. In 1 Chronicles 21:1, Satan incites David to take a census of Israel, and in Zechariah 3:1-2, Satan is an accuser of the high priest Joshua. However, in these instances, Satan is not depicted as an independent, malevolent force opposed to God but rather as a figure functioning within the divine order.

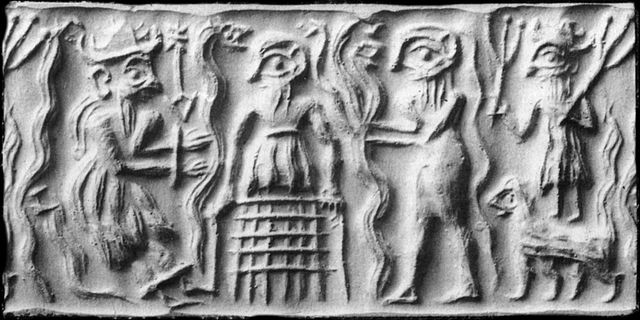

During the intertestamental period, Jewish thought began to develop a more distinct and powerful concept of Satan as a cosmic adversary. Influenced by Persian Zoroastrianism and Hellenistic dualism, Jewish apocalyptic literature began to portray Satan as a leader of fallen angels and demonic forces in rebellion against God. Texts such as Enoch and the Book of Jubilees contributed to this evolving portrayal of Satan. In these writings, Satan (or analogous figures like Mastema in the Book of Jubilees) is depicted as the embodiment of evil, leading a cosmic struggle against God and His angels.

Jewish Apocalyptic Literature and the Development of Satan

Jewish apocalyptic literature from the intertestamental period played a crucial role in the development of the concept of Satan as a distinct entity. Among the most influential of these texts is , a collection of writings composed between the 3rd century BCE and the 1st century BCE. 1 Enoch introduces the idea of fallen angels, known as the Watchers, who rebel against God under the leadership of figures like Azazel and Semjaza. These angels are punished and confined, prefiguring the later NT depiction of Satan as the leader of rebellious spirits. 1 Enoch also describes the final judgment, where sinners and fallen angels are cast into a fiery pit, foreshadowing the Christian concept of Hell.

Another significant text is the Book of Jubilees, written in the 2nd century BCE. Jubilees expands upon stories from Genesis and Exodus, emphasizing the dualistic struggle between good and evil. It introduces Mastema, a figure closely associated with Satan, who acts as an accuser and tempter, reflecting the evolving understanding of Satan as a more active and personal adversary. The Book of Jubilees contributes to the development of demonology and the concept of a cosmic battle between the forces of good and evil.

The ,Testament of the Twelve Patriarchs likely composed between the 2nd century BCE and the 1st century BCE, also reflects the dualistic worldview that became more prominent during this period. This collection of the final speeches of Jacob’s twelve sons often addresses themes of virtue, vice, and eschatological judgment. The text introduces the idea of opposing spirits or angels, some associated with Satan, which would influence later Christian teachings on spiritual warfare.

The, Assumption of Moses dating from the 1st century BCE to the 1st century CE, contains apocalyptic prophecies attributed to Moses. It speaks of a coming judgment where the righteous will be rewarded, and the wicked, associated with demonic powers, will be punished. Although Satan is not explicitly named, the text aligns with the evolving understanding of cosmic evil and its opposition to God.

Another important work is Esdras (also known as 4 Ezra), composed in the late 1st century CE, likely after the destruction of the Second Temple in 70 CE. This apocalyptic text deals with divine justice, the fate of the righteous and the wicked, and the coming of the Messianic age. While Satan is not explicitly mentioned, the themes of judgment and opposition to God’s will align with the developing concept of Satan as a cosmic adversary.

Lastly, although part of the Hebrew Bible, the Book of Daniel (especially its later chapters, composed during the Hellenistic period) is often considered within the context of apocalyptic literature. Daniel introduces apocalyptic visions and prophecies that include themes of cosmic struggle and the ultimate triumph of God’s kingdom over evil forces. While Satan is not directly named, Daniel sets the stage for later developments in eschatology and the understanding of Satan’s role in the end times.

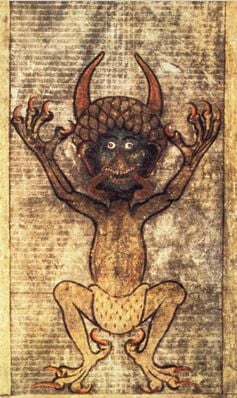

Satan in the New Testament

By the time of the NT, Satan had emerged as a real and powerful being, the personification of evil, and the chief opponent of God and humanity. He is depicted as the ruler of a kingdom of darkness, actively working to thwart God’s plans. For example, in the Gospels, Satan tempts Jesus in the wilderness (Matthew 4:1-11; Luke 4:1-13), showing his role as a tempter and deceiver. Jesus refers to Satan as “the prince of this world” (John 12:31) and “the father of lies” (John 8:44), underscoring his role as a leader of evil and deception.

In the NT, Satan is also closely associated with Hell and eternal punishment. The Book of Revelation describes Satan as the great dragon, the ancient serpent who leads the whole world astray, and his ultimate fate is to be cast into the lake of fire, a place of eternal torment (Revelation 20:10). This depiction ties the concept of Hell with the final defeat and punishment of evil, embodied in Satan.

Moreover, the NT frequently portrays Satan as a threat to believers, seeking to lead them away from faith. The Apostle Paul refers to Satan as the “god of this age” who blinds the minds of unbelievers (2 Corinthians 4:4), and Peter warns that Satan prowls around like a roaring lion, looking for someone to devour (1 Peter 5:8). These depictions of Satan as an active and personal adversary reflect the full development of his character from the more ambiguous references in the OT.

Jesus’s Teachings on Hell

In the NT, Jesus expands upon and intensifies the understanding of Hell as a place of divine judgment and eternal punishment. Hell is portrayed as a place of fire, darkness, and separation from God, reserved for the wicked after the final judgment. For example, in Matthew 5:22, 29-30, Jesus warns of the danger of hellfire for those who commit sins such as anger and lust. Similarly, in Matthew 10:28, He warns that one should fear God, who has the power to destroy both soul and body in Hell (Gehenna). These teachings emphasize the seriousness of sin and the ultimate consequences of moral choices.

Moreover, in passages like Mark 9:43-48, Jesus uses vivid imagery to describe Hell as a place where “the worm does not die, and the fire is not quenched,” highlighting the eternal nature of Hell’s punishment. In the parable of the sheep and the goats (Matthew 25:41, 46), Jesus speaks of eternal punishment for the wicked, contrasting it with eternal life for the righteous. This marked a significant departure from the OT concept of Sheol and reflects the evolving Jewish and Christian understanding of the afterlife.