The Prophet Daniel

Table of Contents

The prophet Daniel

Born in Judea was a young elite adult when he was exiled to Babylon. Part of an elite group of scholars who the Babylonians under Darius wanted to use as administrators for their Empire. He became , according to the Book of Daniel , an important advisor to Kings Darius ,

Daniel’s History

Daniel’s service under four kings The Persian takeover of Babylon Daniel’s service under four kings:

In the Book of Daniel, he is portrayed as serving under four kings:

Nebuchadnezzar II (Babylonian) Belshazzar (Babylonian) Darius the Mede (often identified with Cyrus the Great or considered a subordinate ruler) Cyrus the Great (Persian)

The Book of Daniel is our primary biblical source for this information. However, it’s important to note that there are historical discrepancies between the biblical account and other historical sources.

The Persian takeover of Babylon:

Main sources:

The Nabonidus Chronicle (part of the Babylonian Chronicles) The Cyrus Cylinder Accounts by Herodotus and Xenophon (Greek historians)

What we know from these sources:

The conquest occurred in 539 BCE. Cyrus the Great led the Persian army. The Babylonian king at the time was Nabonidus, not Belshazzar (who was Nabonidus’ son and co-regent). The Persians diverted the Euphrates River and entered the city through the riverbed. Babylon fell with minimal resistance. Cyrus presented himself as a liberator rather than a conqueror.

The Nabonidus Chronicle

This provides a relatively contemporary account, stating that Babylon fell “without battle” on October 12, 539 BCE. The Cyrus Cylinder, while propagandistic, confirms Cyrus’ policy of religious tolerance and his efforts to portray himself as a legitimate ruler. It’s worth noting that the accounts in Daniel differ from these historical sources in several ways, particularly in the portrayal of Belshazzar as the last king of Babylon and the introduction of “Darius the Mede” as a ruler between the Babylonian and Persian periods. The discrepancies between the biblical account and other historical sources have led to much scholarly debate about the historical accuracy and dating of the Book of Daniel. Many scholars consider it to be a product of the 2nd century BCE, reflecting later interpretations of these historical events.

Are Darius the Mede and Cyrus the Great the same person?

There’s no scholarly consensus on this, but here are the main viewpoints: a) Different individuals: Many scholars maintain that they were separate individuals, with Darius being a subordinate ruler under Cyrus. b) Same person: Some scholars argue that “Darius the Mede” is another name or title for Cyrus the Great. c) Literary creation: Some scholars suggest that Darius the Mede is a fictional character, possibly conflating various historical figures.

Were they Persian or Babylonian?

Cyrus the Great was definitely Persian. He was the founder of the Achaemenid Empire. Darius the Mede, as described in the Book of Daniel, is presented as a Median ruler. The Medes were a distinct group from the Persians, though they were eventually incorporated into the Persian Empire. Neither was Babylonian. The Persians (led by Cyrus) conquered Babylon from the Babylonians.

Debate among scholars:

There is indeed significant debate among scholars about Darius the Mede. The main issues are: a) Historical evidence: There’s no clear extra-biblical evidence for a figure matching the description of Darius the Mede. b) Chronological issues: The Book of Daniel places Darius the Mede between the Babylonian and Persian periods, which doesn’t align with other historical sources. c) Identification theories: Some scholars have tried to identify Darius the Mede with known historical figures:

- Cyrus the Great

- Gubaru (or Ugbaru), a general who ledCyrus’s forces into Babylon

- Cambyses II, son of Cyrus, who may have ruled Babylon as his father’s subordinate

Literary function:

Some scholars argue that Darius the Mede serves a literary or theological purpose in the Book of Daniel rather than being a strictly historical figure.

Dating of Daniel:

The debate about Darius the Mede is part of a larger scholarly discussion concerning the dating of the Book of Daniel and the degree to which it accurately reflects the historical period it describes. Scholarly consensus generally dates the composition of the Book of Daniel to the 2nd century BCE, particularly around 167-164 BCE, during the Maccabean revolt against the Seleucid Empire. This period is marked by the persecution of Jews under Antiochus IV Epiphanes, and many scholars interpret the book’s apocalyptic visions as a response to this historical context.

One of the significant historical discrepancies in the Book of Daniel involves the portrayal of the last kings of Babylon. According to historical records, Nabonidus was the last king of Babylon, reigning from 556 to 539 BCE. His son, Belshazzar, acted as regent in Babylon during his father’s absence but was never officially king. The Book of Daniel, however, presents Belshazzar as the last king, who is overthrown by Darius the Mede after the fall of Babylon.

This account conflicts with known historical events. Babylon was conquered by Cyrus the Great of Persia in 539 BCE, and no historical evidence supports the existence of a ruler named Darius the Mede during this period. The confusion in the Book of Daniel might stem from a conflation of various historical figures, such as Cyrus the Great and Gubaru (a governor under Cyrus), or it might reflect the author’s reliance on incomplete or confused historical sources.

The merging of these figures and the resulting chronological and historical inaccuracies highlight the complexities of reconciling biblical narratives with other historical records. These issues are central to ongoing scholarly debates about the historical reliability of the Book of Daniel, its composition, and its intended purpose. The text remains a crucial point of study for understanding the intersection of faith, history, and literature in the ancient world, with particular attention to the challenges of dating and verifying the events it describes.

What happened to Daniel?

Did he return to Judea? The Book of Daniel doesn’t provide explicit information about Daniel’s final fate or whether he returned to Judea. However, we can piece together some information from the text and make some inferences:

Last mention in the book:

The last clear mention of Daniel’s activities is in Daniel 10:1, which states that he received a vision in the third year of Cyrus, king of Persia (around 536 BCE). Age considerations: If we follow the chronology in the book, Daniel would have been quite elderly by this time. He was taken to Babylon as a young man during Nebuchadnezzar’s reign (around 605 BCE), so by the time of Cyrus, he would have been in his 80s or older.

No mention of return:

Unlike other biblical figures such as Ezra or Nehemiah, there’s no account of Daniel returning to Judea with the other exiles when Cyrus allowed them to go back.

Tradition and speculation

Some Jewish and Christian traditions suggest that Daniel remained in Persia, possibly in a high-ranking position, for the rest of his life. There are even traditions that point to a supposed tomb of Daniel in Susa (modern-day Iran). Historical context: The Edict of Cyrus in 538 BCE allowed Jews to return to Jerusalem and rebuild the Temple. While many Jews did return, others remained in Babylon and other parts of the Persian Empire. Given Daniel’s advanced age and possible high position in the Persian court, it’s plausible that he might have stayed.

Biblical silence:

The fact that neither the Book of Daniel nor other biblical texts mention Daniel returning to Judea might suggest that he didn’t make this journey. It’s important to note that this is largely speculative. The biblical text simply doesn’t tell us what happened to Daniel in his final years or where he ended his life. The silence on this matter has led to various traditions and interpretations, but we don’t have concrete historical evidence one way or the other. This uncertainty about Daniel’s fate is not uncommon for biblical figures. Many prominent characters in the Bible have unclear endings to their stories, which has often led to the development of extra-biblical traditions and legends about their later lives.

Do we have any accounts of people traveling between Babylon and Judea.

Biblical accounts: The books of Ezra and Nehemiah provide some information about the journey from Babylon to Jerusalem. For example:

Ezra 7:9 mentions that the journey from Babylon to Jerusalem took about four months. Ezra 8:15-31 describes preparations for the journey and mentions stopping at the Ahava Canal before setting out.

Archaeological evidence: The Royal Road, established by the Persian Empire, connected Susa to Sardis and passed near Jerusalem. While not a direct route from Babylon, it gives us an idea of established travel routes in the region. Assyrian and Babylonian records: These sometimes mention military campaigns that traversed the region, giving insight into routes and travel times. Herodotus: While not specifically about Babylon to Judea, Herodotus provides information about travel in the Persian Empire, including distances and travel times. Elephantine papyri: These 5th century BCE documents from Egypt mention travel between Egypt and Judea, which can give some context to travel in the region.

Route: The most likely route would have followed the Euphrates River northwest, then turned southwest through Syria and down the Mediterranean coast. Distance: The journey was approximately 900 miles (1,448 km). Duration: As mentioned in Ezra, the journey typically took about four months. Dangers: Travelers faced risks from bandits, harsh terrain, and extreme weather. Preparations: Ezra’s account shows that significant preparations were needed, including gathering supplies and people. Rest stops: There were likely established caravanserais (inns) along major routes for travelers to rest and resupply. Official support: Those traveling on official business might have had access to the Persian imperial postal system, which maintained way stations and fresh horses. Seasonal considerations: Travel was likely easier in spring and fall, avoiding the extreme heat of summer and potential flooding in winter and early spring.

What was the Ahava canal

The Ahava Canal, mentioned in the Book of Ezra, is an interesting but somewhat mysterious geographical feature. Here’s what we know about it:

Biblical Reference: The primary mention of the Ahava Canal is in Ezra 8:15-31. It’s described as a place where Ezra gathered the returning exiles before their journey to Jerusalem. Location: The exact location of the Ahava Canal is uncertain. It was somewhere between Babylon and Jerusalem, likely closer to Babylon. Some scholars suggest it might have been:

A canal branching off from the Euphrates River A town named after a canal A gathering point near a body of water

Function in Ezra’s journey:

It served as an assembly point for the group of exiles returning to Jerusalem. Ezra used this location to organize the people and supplies for the journey. It was also where Ezra proclaimed a fast and sought God’s protection for their journey.

Possible meanings: The name “Ahava” in Hebrew can mean “water” or “river,” which fits with it being a canal or water source. Historical context: Mesopotamia was known for its complex system of canals for irrigation and transportation. The Ahava Canal was likely part of this network. Scholarly debate: There’s no consensus on its exact nature or location. Some scholars have tried to identify it with known waterways or settlements, but these identifications remain speculative. Significance: While its exact location is unknown, the Ahava Canal’s mention provides insight into the logistics of the return from exile, showing how leaders like Ezra organized large groups for long journeys. Lack of extra-biblical sources: Currently, we don’t have any non-biblical ancient sources that mention the Ahava Canal by name, which adds to the difficulty in pinpointing its location or nature.

The Ahava Canal, therefore, remains a somewhat enigmatic geographical feature. Its mention in Ezra gives us a glimpse into the practicalities of the return from exile, but many details about it remain unclear. This is not uncommon for many locations mentioned in ancient texts, where our understanding is often limited by the available historical and archaeological evidence.

Learning of the Chaldeans.

The tension between his Jewish learning and his new role is a constant theme in the book.

Languages:

Aramaic: The lingua franca of the Babylonian Empire Akkadian: The traditional language of Babylonian scholarship Possibly some knowledge of Sumerian, for accessing older texts

Literature:

Epic poetry like the Enuma Elish (Babylonian creation myth) Historical chronicles and royal inscriptions Religious texts and hymns Wisdom literature and proverbs

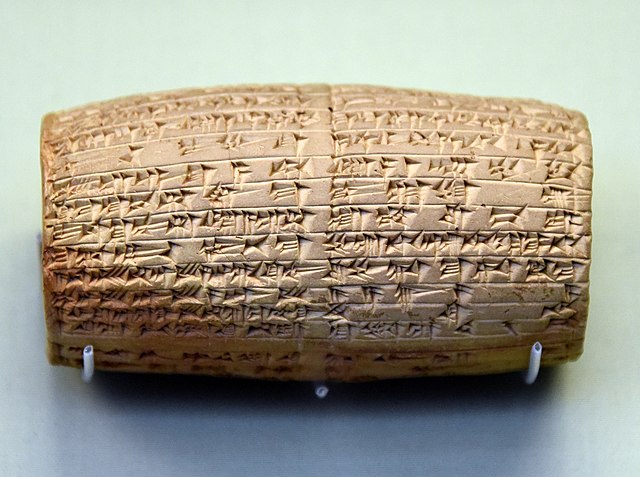

Writing Systems:

Cuneiform script, used for both Akkadian and Sumerian

Sciences:

Astronomy and astrology (which were closely linked in Babylonian culture) Mathematics, including their sexagesimal (base-60) number system Medicine and divination practices

Religious Studies:

Babylonian pantheon and mythology Ritual practices and temple customs

Political Studies:

Structure of the Babylonian government and court Diplomatic protocols and international relations History of Babylonian kings and their conquests Laws and judicial system, possibly including study of the Code of Hammurabi

Arts:

Music theory and instruments Visual arts, including sculpture and bas-relief Architecture, especially as it related to temples and palaces

Etiquette and Court Protocol:

Proper behavior in the presence of royalty Customs and manners of Babylonian nobility

Daniel’s four Dream interpretations

Nebuchadnezzar’s Dream of the Great Statue (Daniel 2:1-45)

Dream: King Nebuchadnezzar dreams of a colossal statue with different parts made of various materials: a head of gold, chest and arms of silver, belly and thighs of bronze, legs of iron, and feet partly of iron and partly of clay. A stone, “cut out without hands,” strikes the statue on its feet, causing the entire statue to collapse and the stone to become a great mountain that fills the whole earth. Interpretation: Daniel explains that the statue represents successive empires. The head of gold is Nebuchadnezzar’s Babylonian empire, the silver represents the Medo-Persian Empire, the bronze symbolizes the Greek Empire, and the iron and clay signify the Roman Empire. The stone represents God’s kingdom, which will ultimately destroy all these kingdoms and endure forever.

Nebuchadnezzar’s Dream of the Great Tree (Daniel 4:1-37)

Dream: Nebuchadnezzar dreams of a great and strong tree that reaches to the heavens and is visible to the ends of the earth. The tree provides shelter and food to all creatures. However, a “watcher” or holy one from heaven decrees that the tree be cut down, leaving only the stump bound with iron and bronze in the grass, and the king’s mind is to be changed to that of a beast for seven times (years). Interpretation: Daniel interprets this dream as a warning to Nebuchadnezzar. The tree represents Nebuchadnezzar himself, who has grown great and powerful. However, because of his pride, he will be driven from human society and live as a beast for seven years until he acknowledges God’s sovereignty. This prophecy comes true, but Nebuchadnezzar is eventually restored to his throne after humbling himself before God.

Belshazzar’s Dream of the Four Beasts (Daniel 7:1-28)

Vision: In a vision during the reign of King Belshazzar, Daniel sees four great beasts rising from the sea: a lion with eagle’s wings, a bear with three ribs in its mouth, a leopard with four wings and four heads, and a terrifying beast with iron teeth, ten horns, and another little horn with eyes and a mouth that speaks arrogantly. Interpretation: The four beasts represent four successive kingdoms, similar to the different materials in Nebuchadnezzar’s statue. The final beast is particularly fearsome, symbolizing a powerful and destructive empire. The vision also includes a scene where “the Ancient of Days” (God) judges these beasts, and “one like a son of man” (often interpreted as a messianic figure) is given eternal dominion and authority.

Daniel’s Vision of the Ram and the Goat (Daniel 8:1-27)

Vision: Daniel sees a ram with two horns, one higher than the other, representing the kings of Media and Persia. A male goat with a prominent horn (representing Greece) attacks the ram, breaking its horns. The goat’s horn is then broken, and four smaller horns arise in its place, followed by a little horn that grows exceedingly powerful and desecrates the temple. Interpretation: The ram symbolizes the Medo-Persian Empire, and the goat represents the Greek Empire, with the prominent horn being Alexander the Great. The four horns that replace the broken horn signify the division of Alexander’s empire among his generals. The little horn represents a future oppressive ruler, often identified as Antiochus IV Epiphanes, who desecrated the Jewish temple, leading to the Maccabean Revolt.

The Writing on the Wall (Daniel 5:1-31)

Event: During a great feast hosted by King Belshazzar, the son of Nebuchadnezzar, a mysterious hand appears and writes a message on the wall of the royal palace. The words written are “Mene, Mene, Tekel, Upharsin.” Belshazzar is terrified, and none of his wise men can interpret the meaning of the writing. The queen mother advises Belshazzar to call for Daniel, known for his ability to interpret divine messages.

Interpretation: Daniel is brought before the king and interprets the writing. He explains that the words are a divine judgment against Belshazzar:

Mene: God has numbered the days of Belshazzar’s reign and brought it to an end. Tekel: Belshazzar has been weighed on the scales and found wanting. Peres (the singular form of Upharsin): Belshazzar’s kingdom will be divided and given to the Medes and Persians. Outcome: That very night, Belshazzar is killed, and Darius the Mede takes over the kingdom, fulfilling the prophecy.

Daniel in the Lion’s Den

Context: Daniel was a high-ranking official in the kingdom of Darius the Mede, who took over Babylon after the fall of Belshazzar. Daniel was highly respected and had gained favor with the king because of his exceptional wisdom and integrity. However, this made other officials jealous, and they sought to find a way to bring him down.

The Plot Against Daniel: Knowing that Daniel was devout in his worship of God, the conspirators devised a plan based on his religious practices. They persuaded King Darius to issue a decree that for 30 days, no one could pray to any god or human except the king. The penalty for disobedience was to be thrown into a den of lions.

Daniel’s Faithfulness: Despite knowing about the decree, Daniel continued his practice of praying to God three times a day, with his windows open toward Jerusalem. The conspirators caught him in the act and reported it to the king.

Daniel in the Lion’s Den: King Darius was distressed because he respected Daniel, but the decree could not be revoked according to the law of the Medes and Persians. Reluctantly, the king ordered Daniel to be thrown into the lions’ den but expressed hope that Daniel’s God would rescue him.

Divine Protection: That night, the king could not sleep and hurried to the lions’ den at dawn. To his great relief, Daniel was unharmed. Daniel told the king that God had sent an angel to shut the lions’ mouths because he was found innocent before God and the king.

Justice and Reward: King Darius ordered that the men who had plotted against Daniel, along with their families, be thrown into the lions’ den, where they were immediately killed. Darius then issued a decree throughout his kingdom that everyone should fear and reverence the God of Daniel, acknowledging God’s power and sovereignty.

Outcome: Daniel continued to prosper during the reign of Darius and the subsequent reign of Cyrus the Persian.

,_f.240_-_BL_Add_MS_11695.jpg)