Some Prophets of the Fall of Judea

Table of Contents

Some prophets of the fall of Judea

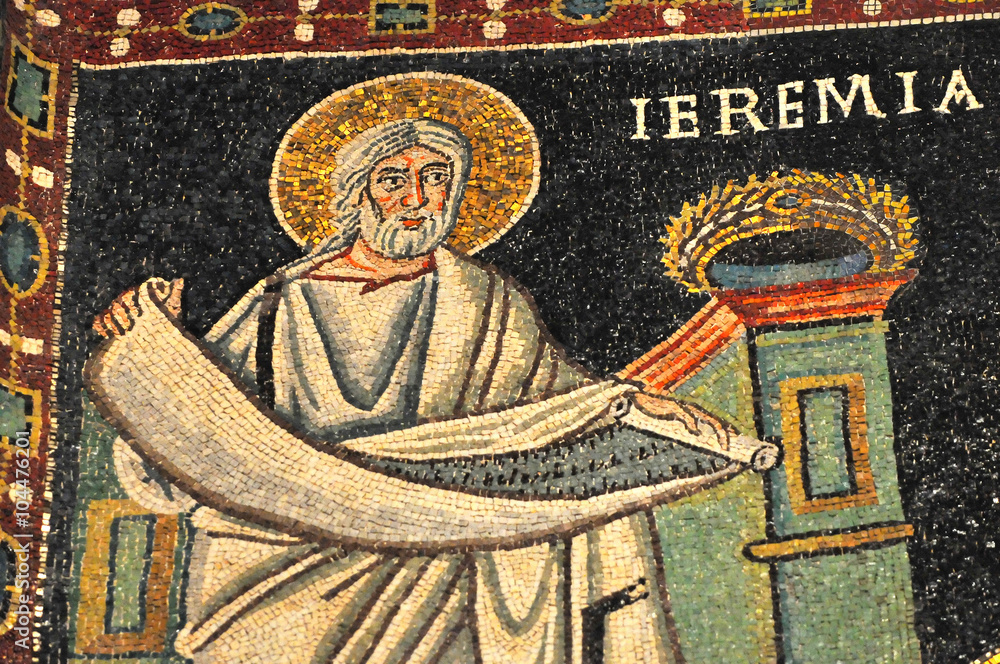

After the fall of Judea Jerimiah chose to stay in the defeated homeland. Following the assasination of Gedaliah he left for Egypt with others who feared revenge attacks.

Jerimiah

*Get yourself ready! Stand up and say to them whatever I command you. Do not be terrified by them, or I will terrify you before them. Today I have made you a fortified city, an iron pillar, and a bronze wall to stand against the whole land—against the kings of Judah, its officials, its priests, and the people of the land. They will fight against you but will not overcome you, for I am with you and will rescue you," declares the Lord (Jer. 1.17-19).

This passage from Jeremiah 1:17-19 encapsulates the divine commissioning of the prophet Jeremiah, wherein God encourages him with powerful metaphors, likening him to a "fortified city," an "iron pillar," and a "bronze wall." Through this symbolic language, God underscores the spiritual strength, resilience, and unyielding protection that He will bestow upon Jeremiah as he embarks on his prophetic mission to confront the leaders and people of Judah. These metaphors are not merely decorative; they are essential to understanding the theological and symbolic dimensions of Jeremiah’s role as a prophet.

In this context, Jeremiah was being prepared to serve as a prophet to the nations, tasked with delivering God’s judgment to the kings, officials, priests, and populace of Judah. The metaphoric language employed by God—describing Jeremiah is deeply evocative, signifying the extraordinary spiritual fortitude with which Jeremiah is endowed. The "fortified city" serves as a potent symbol of the divine protection that will enable Jeremiah to withstand the hostility and resistance of those to whom he is sent to prophesy. This fortification is not passive but rather active, embodying Jeremiah’s role as a resilient bulwark against the pervasive moral and spiritual decay of Judah. God’s assurance, "They will fight against you but will not overcome you, for I am with you and will rescue you" (Jer. 1.19), emphasizes the inviolability of Jeremiah’s mission, reinforcing that, despite fierce opposition, his prophetic work is under the aegis of divine protection.

Theologically, this passage raises profound questions about the nature of divine calling and the ways in which God equips His messengers. The use of such powerful imagery not only conveys the enormity of Jeremiah’s task but also prefigures the larger narrative of divine sovereignty, wherein God’s purposes is achieved through agents who, though they may face severe challenges, are divinely empowered to fulfill their mission. The "fortified city" metaphor anticipates the broader theme of God utilizing foreign nations, such as Babylon, as instruments of judgment—a theme that pervades the prophetic literature, including the later texts of Jeremiah.

This passage also finds resonance within the broader prophetic tradition, where God frequently employs metaphorical language to convey the empowerment and protection of His chosen prophets. Jeremiah’s fortification aligns with the experiences of other prophets who, despite encountering significant opposition, were sustained by divine strength. The use of these metaphors serves as a didactic tool, illustrating that those who are called by God are endowed with the necessary spiritual and moral fortitude to carry out their divine mandates, regardless of the challenges they encounter.

Examining the impact of this passage on its original audience, the imagery of a "fortified city" would have been a powerful and evocative symbol, particularly for the people of Judah with it's main city being Jereusalem. This metaphor would have underscored the seriousness of Jeremiah’s prophetic mission and the divine authority behind his words, serving both as a warning of impending judgment and as a reminder of God’s protective presence for those who remain faithful and within his city.

In another passage from the Book of Jeremiah the prophet addresses the people of Judah regarding their unfaithfulness and idolatry. Here, the reference to Memphis and Tahpanhes—prominent cities in Egypt—functions symbolically to critique Judah’s reliance on foreign alliances rather than on God. The imagery of the "men of Memphis and Tahpanhes cracking your skull" serves as a strong metaphor for the consequences of these alliances, suggesting that such dependence on Egypt has led to Judah’s downfall. The rhetorical question

Have you not brought this on yourselves by forsaking the Lord your God when he led you in the way?" connects Judah’s suffering directly with their abandonment of divine guidance in favor of political expediency.

The imagery of "drinking water from the Nile" and "from the Euphrates" further critiques Judah’s political alliances with Egypt and Assyria, respectively. In the context of ancient Near Eastern politics, "drinking water" from a foreign river symbolized entering into a political alliance or reliance on that nation for security. By engaging in such alliances, Judah is depicted as forsaking its covenantal relationship with God, leading to its moral and spiritual decline. The subsequent verses elucidate that Judah’s "wickedness will punish" them and their "backsliding will rebuke" them, underscoring the self-inflicted nature of their suffering due to their unfaithfulness.

Jeremiah’s repeated call for repentance, directed toward both Israel and Judah, despite the historical reality that the northern kingdom of Israel had already been dispersed by the Assyrians, serves multiple symbolic and theological purposes. First, it underscores the unity of God’s covenant people, with "Israel" symbolically representing all twelve tribes, despite the political and geographical realitiesafter the 10 tribes were dispersed into the Assyrian Empire. Second, it reflects the hope for the restoration and reunification of the dispersed tribes under God’s rule—a recurring theme in prophetic literature. Third, addressing Israel serves as a didactic reminder to Judah of the consequences of unfaithfulness, using Israel’s fate as a cautionary example.

In conclusion, the passages from Jeremiah analyzed here demonstrate the intricate interplay of metaphor, historical context, and theological reflection. The "fortified city" metaphor in Jeremiah 1:17-19 encapsulates the divine protection and resilience bestowed upon the prophet, serving as a powerful symbol of God’s enduring presence and support. Similarly, the critique of Judah’s alliances with Egypt and Assyria in chapter 2 underscores the folly of forsaking God for political expediency. Together, these texts reveal a complex theological narrative that addresses the themes of divine sovereignty, justice, and the call to repentance, all within the context of the impending judgment on Judah.

Work Cited:

The Holy Bible. New International Version, Zondervan, 2011.

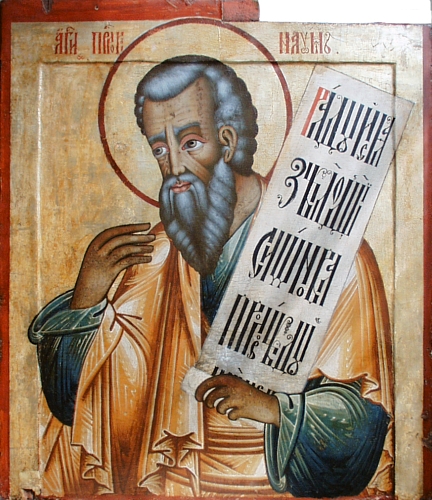

Nahum - Prophecies against Assyria

Nahum 1 in the Old Testament presents a prophecy against Nineveh, the Assyrian Empire's capital. Nahum's prediction of Nineveh's fall holds significance in several key aspects:

Nineveh's Power and Influence:

Nineveh, as the Assyrian Empire's capital, represented one of the ancient Near East's most formidable powers. It had captured and destroyed the northern kingdom of Israel (around 722 BC). Nahum vividly describes this power: "Are you better than Thebes, situated on the Nile, with water around her? The river was her defense, the waters her wall" (Nahum 3:8).

Judgment on a Wicked Nation:

The fall of Nineveh signified God's judgment on a wicked nation. Nahum declares: "The Lord is a jealous and avenging God; the Lord takes vengeance and is filled with wrath. The Lord takes vengeance on his foes and vents his wrath against his enemies" (Nahum 1:2).

Fulfillment of Prophecy:

Nahum prophesied Nineveh's destruction in detail: "The gates of the rivers are opened, and the palace is dissolved" (Nahum 2:6). This prophecy came to pass in 612 BC when a coalition sacked Nineveh.

Encouragement for the Oppressed:

Nahum's prophecy offered hope to the oppressed: "The Lord is good, a refuge in times of trouble. He cares for those who trust in him, but with an overwhelming flood he will make an end of Nineveh; he will pursue his foes into darkness" (Nahum 1:7-8).

Historical Context:

Nahum references historical events, such as the fall of Thebes: "Are you better than Thebes… Yet she was taken captive and went into exile" (Nahum 3:8,10).

In conclusion, Nahum's prophecy about Nineveh's fall represented a powerful statement of divine justice. As Nahum proclaimed: "Look, there on the mountains, the feet of one who brings good news, who proclaims peace! Celebrate your festivals, Judah, and fulfill your vows. No more will the wicked invade you; they will be completely destroyed" (Nahum 1:15).

Fall of Thebes

Nahum references the fall of Thebes (Luxor) in Egypt to the last Assyrian King, Ashurbanipal. He writes: "Are you better than Thebes, situated on the Nile, with water around her? The river was her defense, the waters her wall. Cush and Egypt were her boundless strength; Put and Libya were among her allies. Yet she was taken captive and went into exile" (Nahum 3:8-10). This example illustrates that even the mightiest cities can succumb to divine judgment, foreshadowing Nineveh's own fate.

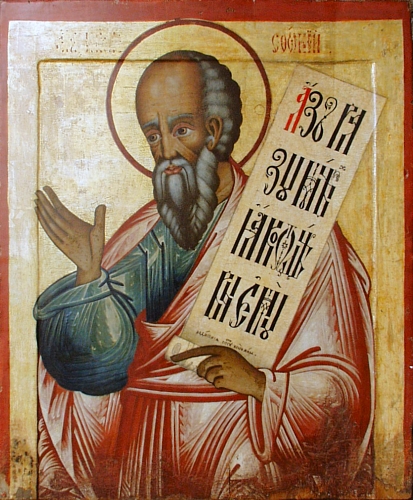

Zephanniah

Zephaniah constitutes a critical segment within the Old Testament, interweaving intricate themes of divine judgment and eschatological hope within the broader prophetic discourse. Central to this discourse is the concept of the "Day of the Lord," a multifaceted eschaton characterized by divine retribution against sin and rebellion. This chapter, through its sophisticated narrative structure, juxtaposes the condemnation of Jerusalem’s moral degeneracy with the eventual promise of restoration, thereby offering a profound theological reflection on the dialectic between divine justice and mercy.

The prophetic invective initiates with a trenchant critique of Jerusalem, epitomized as a "rebellious and defiled" city (Zeph. 3.1). The prophet’s rhetoric employs stark, vivid imagery to accentuate the systemic and pervasive corruption endemic to the urban polity. The denunciation is not limited to the general populace but extends to the city’s leadership, encompassing prophets and priests, who are excoriated for their egregious dereliction of their sacerdotal duties and their flagrant subversion of divine law: "Her officials within her are roaring lions; her judges are evening wolves that leave nothing till the morning" (Zeph. 3.3). Despite the consistent manifestation of divine righteousness, the city remains obdurate in its iniquity, a motif that reverberates throughout the initial pericope (Zeph. 3.1-7).

The narrative subsequently expands its purview to articulate a universal judgment, wherein the divine fiat to "gather nations" and "assemble kingdoms" (Zeph. 3.8) is promulgated. This eschatological vision is rendered through the metaphor of a purifying conflagration, an allegory designed to symbolize the expurgation of global iniquity. The prophetic rhetoric underscores the severity and universality of this impending divine retribution: "In the fire of my jealousy all the earth shall be consumed" (Zeph. 3.8). The employment of fire as a metaphor is emblematic of the comprehensive and all-encompassing nature of divine judgment.

Interwoven within this foreboding proclamation is a soteriological motif that offers a countervailing promise of restoration and purification. The divine assurance to "change the speech of the peoples to a pure speech" (Zeph. 3.9) signifies not merely a superficial alteration but rather a profound transformation of the collective ethos, facilitating the universal invocation of the divine name and the establishment of a unified, pious community. This purification of language serves as a potent symbol of spiritual renewal, underscoring the holistic and transformative nature of divine restoration. The concept of a remnant, defined by their humility and steadfast fidelity, emerges as a pivotal theme, encapsulating the eschatological hope that follows divine judgment: "For I will leave in the midst of you a people humble and lowly. They shall seek refuge in the name of the Lord" (Zeph. 3.12).

The chapter’s denouement envisions a triumphant restoration of Jerusalem, characterized by an exhortation to Zion to exult in the abrogation of divine punishment and the subjugation of adversaries. The depiction of God as a "mighty one who will save" (Zeph. 3.17) invokes the imagery of divine warriorship, a motif that emphasizes both the omnipotence and benevolence of the deity. This eschatological vision culminates in the ingathering of the diaspora and the transmutation of ignominy into renown, signifying a comprehensive renewal of both the community and its sociopolitical landscape: "I will make you renowned and praised among all the peoples of the earth, when I restore your fortunes before your eyes" (Zeph. 3.20).

Although Zephaniah 3 does not overtly reference the Assyrian Empire, the specter of Assyrian hegemony and its deleterious impact on Judah operates as an implicit substratum to the prophetic text. The themes of judgment and restoration articulated in the chapter resonate with the broader geopolitical context, including the Assyrian incursions and their consequent ramifications for Jerusalem. The divine promise to gather the scattered likely alludes to the anticipated restoration of those exiled or displaced by such invasions, thus symbolizing divine fidelity to the covenantal promises.

The conspicuous absence of direct references to the Assyrians in Zephaniah 3 is indicative of the prophet’s intent to foreground the internal moral and spiritual deficiencies of Jerusalem rather than external geopolitical threats. Nonetheless, the pervasive influence of foreign dominion, exemplified by Assyrian imperialism, on Judah’s political and religious milieu is a critical contextual element for comprehending the depth of Jerusalem’s corruption and the subsequent necessity for divine intervention and the eventual restoration.

In summation, Zephaniah 3 presents a sophisticated theological discourse that intricately weaves together themes of judgment and eschatological hope. The chapter’s rhetorical progression from the denunciation of Jerusalem’s moral turpitude to the assurance of restoration for a purified remnant reflects a broader theological paradigm that transcends the immediate historical context. While the prophecy is indubitably informed by the socio-political realities of Assyrian domination, it ultimately articulates universal principles of divine justice and mercy, with an enduring emphasis on the moral and spiritual regeneration of the covenantal community. This prophetic vision, in its profundity, continues to resonate as a timeless reflection on the dynamics of divine-human interaction.

Work Cited:

The Holy Bible. New International Version, Zondervan, 2011.

Habakkuk

Figure 4: 18 century icon painter - Iconostasis of Transfiguration church, Kizhi monastery, Karelia,

Habakkuk 1 presents a profound theodicy, wherein the prophet Habakkuk articulates his dismay and perplexity regarding the pervasive injustice and violence that dominate Judah. The prophet confronts the apparent silence and inactivity of God in the face of such egregious evil, questioning the divine tolerance of iniquity. In response, God discloses a startling revelation: He is raising up the Babylonians (Chaldeans), a nation notorious for its ferocity and ruthlessness, to serve as the instrument of divine judgment against Judah’s transgressions.

Scholarly Perspectives on Habakkuk 1 and the Babylonian Prophecy:

The historical context of Habakkuk’s prophecy is generally situated in the late 7th century BCE, a period marked by the burgeoning ascendancy of the Babylonian Empire. This timeline likely corresponds to the reign of King Jehoiakim of Judah (609-598 BCE), a time when Babylonian power was beginning to consolidate in the Near Eastern region. Under the leadership of King Nebuchadnezzar, the Babylonian Empire would eventually subjugate Jerusalem in 586 BCE, leading to the catastrophic destruction of the Temple and the subsequent Babylonian exile—a pivotal event in Israelite history.

The specificity of the prophetic pronouncement in Habakkuk 1:6, "I am raising up the Babylonians," warrants particular scholarly attention due to its direct identification of the agent of divine judgment. This explicit reference enhances the prophetic credibility of the text, as the subsequent historical developments align precisely with the prophecy. Some scholars interpret this specificity as indicative of a divine revelation that provided Habakkuk with profound insight into the geopolitical dynamics of his era, potentially anticipating the Babylonian threat before it became an overt menace to Judah. This perspective suggests that Habakkuk possessed an acute awareness of the political and military shifts occurring in the region, an understanding that was divinely inspired and prophetically articulated.

Theologically, this passage presents a complex and challenging notion: the employment of a pagan and violently oppressive nation, such as Babylon, to execute divine judgment upon Judah. This raises intricate questions regarding the nature of divine justice and governance, particularly in relation to the use of morally corrupt nations as instruments of God's will. Habakkuk's dialogue with God reflects a deep struggle to reconcile the holiness of God with His use of a nation that is ostensibly more wicked than Judah itself to carry out His punitive measures. This tension is emblematic of the broader biblical discourse on theodicy, wherein God’s sovereignty is asserted through His prerogative to use various nations and historical events to fulfill His purposes, irrespective of the moral character of those nations.

This prophecy is consonant with the wider prophetic tradition in the Old Testament, wherein God frequently announces impending judgment through the agency of specific nations. The invocation of the Babylonians in Habakkuk aligns with the prophetic messages of other contemporaneous texts, such as those found in Jeremiah, Isaiah, and Ezekiel, which similarly forewarn of Babylon's rise and its integral role in God’s overarching plan. Some scholars posit that the precise nature of Habakkuk's prediction may have functioned as a didactic tool, intended to prepare the people of Judah for the impending crisis and to exhort them toward repentance before the onset of divine retribution.

For the original audience of Habakkuk’s prophecy, the reference to the Babylonians would have been profoundly alarming. The Babylonians were renowned for their military prowess and brutal conquests, which would have instilled a sense of impending doom and urgency among the people of Judah. This prophecy would likely have amplified the existential dread and compelled the populace to reflect seriously on the gravity of their situation and the necessity of returning to covenantal faithfulness.

In conclusion, scholarly interpretations of Habakkuk 1 underscore the historical veracity and theological significance of the Babylonian prophecy. The passage is understood to accurately reflect the geopolitical realities of its time while simultaneously grappling with profound questions about divine justice and theodicy. The explicit identification of Babylon as the instrument of divine judgment not only underscores the severity of God's impending punishment on Judah but also sets the stage for the deeper theological inquiries into faith, doubt, and divine sovereignty that permeate the rest of the book.

Work Cited:

The Holy Bible. New International Version, Zondervan, 2011.