October 2020 Blog

Table of Contents

Archaeology of Ideas: The World Library 19/10/20

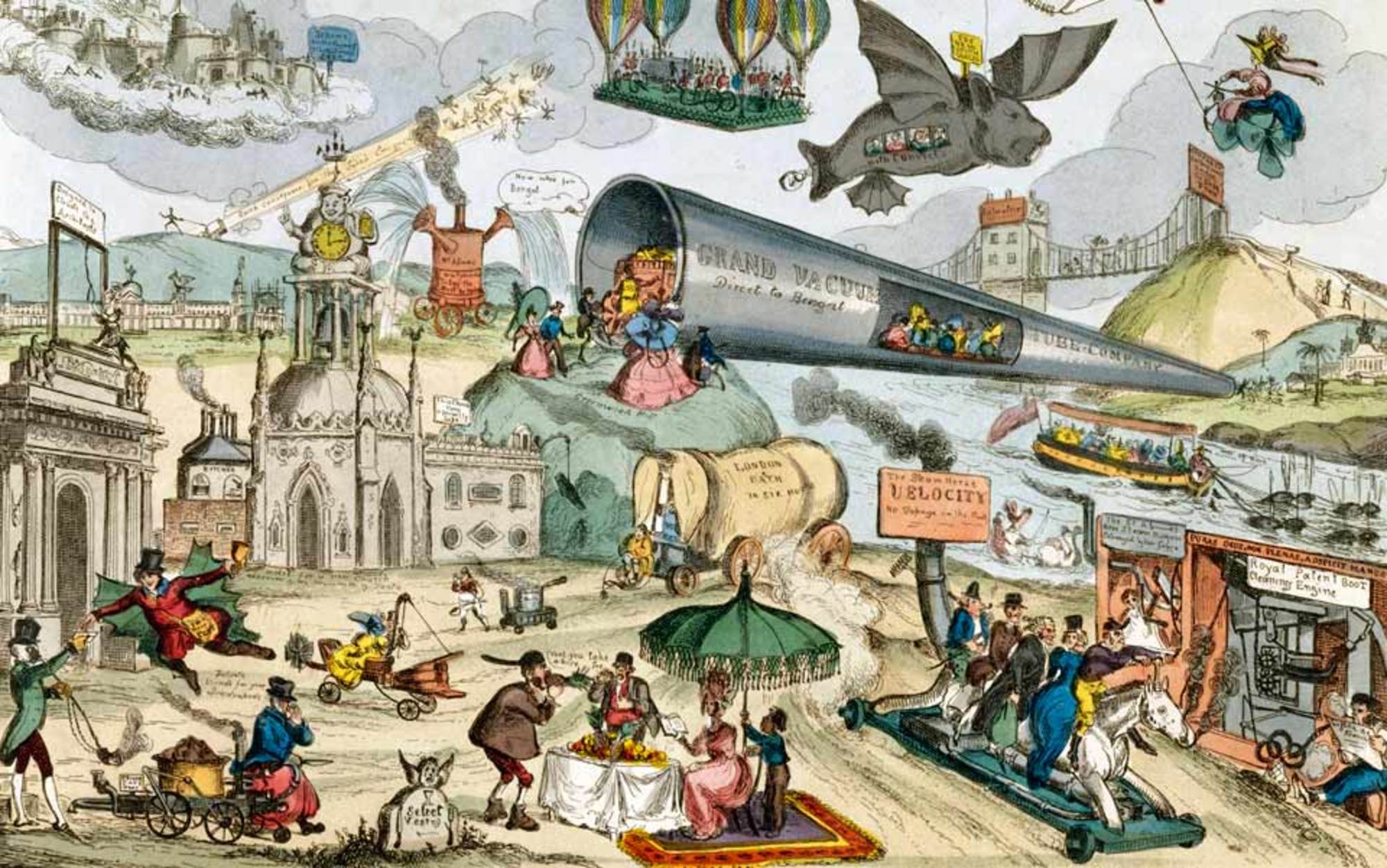

Figure 1: Victorian information flows

How do we visualise the internet? Do metaphors that attempt to conceptualise the web, help drive it's development? When I first started using the internet regularly in 1997, one of the ideas that interested me was that the web would grant universal access to knowledge that had previously been difficult to reach. It was summed up by the phrase "Information wants to be free" . Although this was vaguely defined it offered a powerful vision of what the world wide web could become. It was based on the idea that knowledge was locked away in inaccessible silos that could now be opened and used by anyone with an internet connection. These silos were said to exist in national libraries , academic institutions, the great collections of art in public museums as well as private databases. The internet would create universal, instant, access to this locked away knowledge that would benefit society greatly. It is arguable that this goal has already been achieved, but what we didn't account for back in 1998 was that society didn't value the easy distribution of knowledge very highly. Nevertheless, the consequences of achieving this "freedom of information" will likely be judged to have been very significant. Analysing slogans is no substitute for the historical analysis of power relations in society. The owners of many of the information silos were unwilling to liberate their profitable data.

The dream of a "World Library" was something that pre-dated the internet age by 100 years. I had assumed that the metaphor of the internet as a universal or world library was without precedent, that it had been developed as a way to promote some of the possibilities of the technologies that had created the network of networks. And then while reading Kathy Peiss's book "Information Hunters: When Librarians, Soldiers, and Spies Banded Together in World War II Europe" (OUP 2020) I learned about some of the ideas that formed the intellectual groundwork that helped create the information society we live in today.

Although information science is often seen as a post–World War II development, its origins may be traced to the turn of the twentieth century, in the pioneering work of Belgians Paul Otlet and Henri La Fontaine, who founded the International Institute of Bibliography in 1895 (renamed the International Federation for Documentation in 1937).

By 1937, a World Congress of Universal Documentation was held in Paris, sponsored by the League of Nations, to consider “the methods and necessities of welding the intellectual resources of this planet into a unified system.” Organisers believed that modern developments—from the growth of applied science and business information to global media and mass education—demanded techniques of universal documentation. Beyond the “traditional idea” of printed documents, newer modes of information sharing, such as “the film, the record, the sample and the model,” would be crucial for research, education, and the economy. The "World Brain" as writer H. G. Wells vividly described it, had a larger political purpose as well. In keeping with the internationalism of the interwar years, Otlet and Wells believed that intellectual cooperation would defeat the forces of nationalism, hatred, and violence. In a time of growing conflict and division, the world brain would advance world peace. The Congress attracted 460 attendees from 45 countries, including a delegation from the United States. After his electrifying speech at the World Congress, Wells promoted this idea on an American lecture tour.

The quotation above is from the opening chapter of the book where the origins of what would become today's information infrastructure are described. While the main purpose of the book is documenting the work of art historians and other experts who were working on systematising collections of knowledge and data for American cultural institutions during and after WW2, what becomes very clear is that long before the internet, the idea of an easily accessible universal library containing all the world's knowledge was already taking shape. Because everything has a history, sometimes bringing the origins of ideas to light can produce new interpretations of contemporary institutions. In Ms Peiss's superb work she quotes Librarian of Congress Archibald MacLeish as saying “the country of the mind must also attack”. The new information systems being built after 1941 were to be an essential tool in the war against fascism, just as the freedom to access information through the internet is a weapon against today's tyrants.

All Souls Day 2020:Slavery and Science

How much do you know about slavery? Maybe you have read a couple of books, enjoyed some novels and seen some films. Well done. It is fairly likely though, that you still know very little. How about medical knowledge gained from the effects of slavery? I knew nothing at all about this subject until Greg Grandin's book "The Empire of Necessity" brought my attention to this, and to many other gaps in my knowledge of the history of slavery. In the book Grandin explores an incident on a slave ship off the coast of Chile in 1805, and uses it to investigate the condition of slavery in the Americas in the early C19 th. He uses a series of complex but interconnected stories that illustrate the status of slavery both then and now. The book is full of incidents that suggested to me that slavery, and its legacy, is still ignored by the countries and groups that benefited from it . The debt remains unpaid. He quotes Ralph Waldo Emerson from 1841 to illustrate that this guilt was recognised at the time.

The “trail of the serpent,” Emerson said, “reaches into all the lucrative professions and practices of man.” “We are all implicated”

The consequences of this deliberate act of forgetting will, I believe, become an issue at the top of the political agenda in many countries. Here is the first reference in Grandin's book to the debt medical knowledge owes to slaves.

For instance, an epidemic of blindness that broke out on the French slaver Rôdeur, which sailed from Bonny Island in 1819 with about seventy-two slaves, helped eye doctors identify important information concerning ophthalmia, or trachoma. The disease appeared not long out to sea, first in the hold among the slaves and then on deck, blinding all the voyagers save one member of the crew. According to a passenger’s account, sightless sailors worked under the direction of the one seeing man “like machines,” tied to the captain with a thick rope. “We were blind—stone blind, drifting like a wreck upon the ocean.” Some sailors went mad and tried to drink themselves to death. Others cursed through the day and night. Still others retired to their hammocks, immobilised. Each “lived in a little dark world of his own, peopled by shadows and phantasms. We did not see the ship, nor the heavens, nor the sea, nor the faces of our comrades.” But they could hear the cries of the slaves in the hold.

This went on for ten days, through storms and calms, until the voyagers heard the sound of another ship. A Spanish slaver, the San Leon, had drifted alongside the Rôdeur. But the entire crew and all the slaves of that ship had been blinded by disease as well: when the sailors of each vessel realised this “horrible coincidence,” they fell into silence, “like that of death.” Eventually the León drifted away and was never heard from again.

The Rôdeur’s one seeing mate managed to pilot the ship to Guadeloupe. By now, a few of the crew members, including the captain, had begun to regain some of their vision. But thirty-nine Africans hadn’t, so before entering the harbour the captain decided to drown them, tying weights to their legs and throwing them overboard. The ship was insured and their loss would be covered. (The practice of insuring slaves and slave ships, which had become common by this point, extended a new kind of economic rationality into the trade, helping slavers decide that a dead slave might be worth more than living labour.) The case of the Rôdeur caught the attention of Sébastien Guillié, director and chief of medicine at Paris’s Royal Institute for Blind Youth. He wrote up his findings and published them in Bibliothèque ophtalmologique, which was then cited in other medical journals.

There are too many possible threads to follow in a short post. But there is one thing everyone can now agree about. Black people have been used as subjects for medical experiment by scientists who would claim allegiance to Enlightenment values. So on this All Souls day 2020 we would do well to remember the victims and especially those enslaved on the Rôdeur.

Figure 2: Horror as entertainment